The history of WuMei passed down from Grandmaster Chee Kim Thong

The legendary Kung Fu Empress

An article by Yap Boh Heong.

Disclaimer

It’s fair to say that there is much mystery surrounding WuMei. There’s even disagreement over her name. Much of the mystery is due to the lack of written records written about her. There could be two reasons for that;

1. Firstly, many records were destroyed when the Southern Shaolin was burnt to the ground.

2. Secondly, which is more relevant, is the fact that WuMei was actively fighting against the Qing. She sought anonymity to prevent the emperor and his spies from tracking her down. Using her real name would have endangered the lives of those close to her. Hence she probably operated under various pseudo-names, meaning that the Southern Shaolin temple kept no records of her activities.

As a result of the lack of written records, the oral history passed down by the late Grandmasters are all there is to go by. However, the more fancy and implausible parts must be filtered out. This article seeks to document the oral history from the late Grandmaster Chee Kim Thong’s lineage of WuMei, which has not been recorded anywhere else until now.

Introduction

WuMei 伍枚 (Ng-Mui in Cantonese), the legendary nun from the Shaolin Temple, has always been an elusive figure that played a significant role in Southern Shaolin martial arts. The anecdote and stories presented here are taken from the oral history of the various arts as taught by Grand Master Chee Kim Thong. The purpose of this article is to shed light on WuMei as a person and to understand her art: WuMei Quan. Some have said that she is merely a legend, but as far as our lineage goes, her art exists, and to an extent, it suggests the actual existence of Wumei.

Early Beginnings

It helps to understand the political and social situation at the time. The historical context in which events took place was during the tumultuous period between the fall of the Ming Dynasty and the establishment of the Qing Dynasty. The Qing military was strong enough to beat the Ming, but not sufficient to control the entire country.

Furthermore, the Manchus of the Qing dynasty was a nomadic race from the plains of northwest China. Although they adopted the system of government of the Ming, they had their own culture, which they imposed on their subjects, e.g., the wearing of pigtails and robes (seen in many Kung Fu movies). As a result, there were many rebellions against the Qing centered around the call to “Overthrow the Qing and restore the Ming.”

China is a large and geographically diverse country. It ranges from the vast plains of the north to the hilly sub-tropical terrain of the south. From the mountains of Tibet in the West and the typhoon lashed coastline of the east. The Qing court and center of power were in Beijing in northern China. Hence the region south of the Yangtze River was considered remote and inaccessible.

The Yangtze river represented a significant obstacle for logistics, although the southern centers of the population like Quandong and Fujian were accessible by sea, the Manchus were a people of the plains; hence, they did not have a strong navy. Neither were they adept at fighting on the hilly, forested, and swampy terrain of the south.

Therefore the Qing made use of the defeated Ming generals through threats and favors (by offering land and control of territories) to control more remote parts of the country, especially the southern provinces of Quandong and Fujian. This led to very complex politics and fragile loyalties with shifting alliances that would often swing from one side to the other (between Ming rebel forces to Qing court).

As a result, the southern part of the country was poorly controlled by the Qing emperor. Ming supporters formed rebel groups that attacked and harassed the Qing forces before the Qing could consolidate their rule over the country. This would put the timeframe between 1644-1662 thereabouts.

Legend has it that WuMei was a member of the Ming court (the General’s daughter). When the Manchus took over, it was customary to slaughter the entire family of the previous emperor (and those loyal to him) to prevent uprisings and rebellion. Their executioner took pity on WuMei, and instead of chopping off her head, they chopped off an arm and let her go (supposedly to provide sufficient blood and gore as evidence that the beheading was done).

WuMei survived and ended up in Southern Shaolin. Some say she spent some time in Wudang, a center for Daoism and related martial arts. When she arrived in Southern Shaolin, her Kung fu was already a high standard. At the time, there were many rebel groups against the Qing. Due to persecution from the Qing army, a lot of the rebels fled south to seek refuge around the Southern Shaolin temple.

In Southern Shaolin

In the earlier period, the temple did help the Qing to gain favors from the emperor. There was another rebellion in the southwestern border, probably by ethnic Tibetan forces, which the appointed Qing generals could not overcome. The temple, hoping to gain favors from the emperor, sent a troop of 128 monks to battle those rebels and succeeded in defeating a much larger force. But instead of gaining the favors they wanted, it caused jealousy and fear at the court. This caused the emperor to turn against Southern Shaolin. After that, Ming supporters (rebels) and martial artists gathered around Southern Shaolin and subsequently took on a more anti-Qing stance. Shaolin also began training non-monks (the rebels) in martial arts. The insurgents raided Qing outposts and supply lines. WuMei played an active role as the leader of the guerrilla raiding parties.

Finally, the Qing emperor, fearful of the growing power of Southern Shaolin, sent an enormous team to destroy it. They succeeded, killing many monks and burning the temple to the ground. WuMei was one of the five elders that survived the massacre and escaped to reform Southern Shaolin.

After a few years, Shaolin was destroyed a 2nd time due to the betrayer monk BakMei, who was among the 5 Elders. Following the 2nd destruction of Southern Shaolin, the others sought revenge against the traitor. However, BakMei was a formidable fighter, and he killed two of the five elders that went after him. According to our oral history, in the end, it was WuMei who hunted him down and killed him. Tired of all the violence, WuMei traveled to Emei Shan (mountain) to seek peace, her last known whereabouts. Is it said that the style Emei Quan may have been founded due to WuMei’s influences, although it is quite different from her creation of WuMei Quan.

The Development of WuMei’s art

Southern Shaolin was already established as a center for Chan Buddhism and the fighting arts. In a time of peace, teaching at the temple would have been divided between religion (Chan Buddhism), healing & medicine, and martial arts. Due to the rebellion, more emphasis would have been given to the martial arts, and the temple probably maintained a high state of Battle Readiness. Hence, the focus on the development of the (Southern) arts to be more combat effective and lethal rather than aesthetics or health.

As the rebellion gained momentum, rebels and martial artists that fought the Qing, gathered around the temple. With the diversity and quality of skilled martial artists in Southern Shaolin, it became an R&D (Research and Development) center for martial arts. Hence, it’s not surprising that this resulted in the vast multitude and diversity of styles of the Southern Martial Arts compared to the relatively few styles from the north.

Imagine WuMei, who was herself persecuted, being thrown into this environment. She had already developed her art to a high degree, no doubt from her stay on Wudang. In these desperate times, and the conducive environment provided by the diverse high-level martial artist in Shaolin, WuMei had the ideal environment to develop her art to the highest degree! She needed her art to be more direct and lethal. Yet she was a woman and one-armed at that. So a direct approach of power vs. power is impractical. Hence she developed the art and tactics to depend on stealth and precision. She also devised techniques that gave her a strategically advantageous position to strike or to evade. Thus her style developed into a close-range fighting system. All this while still maintaining a soft and internal engine that can deliver tremendous power at short range. The art of WuMei may look soft, but her strikes are sharp and penetrating. WuMei is also unusual for a soft-internal art as the forms are not performed slowly, and it practices hand/arm conditioning.

At Shaolin, she had more than enough opportunities to test, spar, and fine-tune her art. Furthermore, she was active in the field leading bands of guerrillas to attack the Qing forces, and these are ideal conditions to apply tactics and strategies mentioned above, These field operations further allowed WuMei to refine her art.

Several stories (in our oral history) mention that WuMei and her guerrilla bands played the role of assassins, despatching cruel and prominent Qing officials. If that is the case, then we can understand why stealth and lethality played such an important role, especially when coupled with the only weapon known to be used by WuMei, the WuMei Needle, this is a slim steel spike that doubles as a hair ornament! So one may say, her art was born and forged in times of war, quite unlike those created in peacetime.

WuMei taught very few students, and very few could grasp her art due to its deep sophistication. It is an extremely challenging art to learn, even compared to other internal arts. However, she did have a few successful students, notably women.

WuMei, in the Present

Chee Kim Thong lineage:

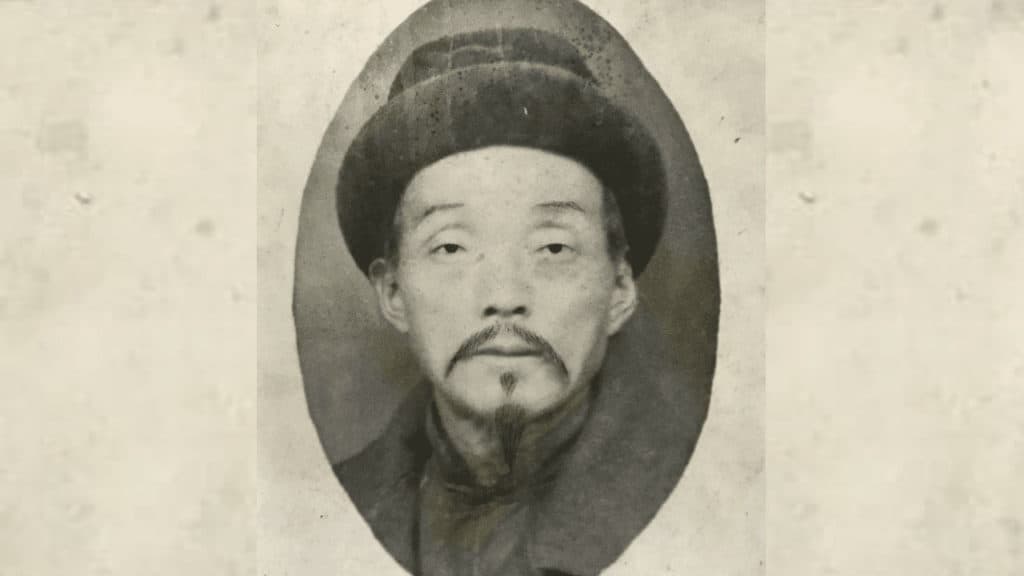

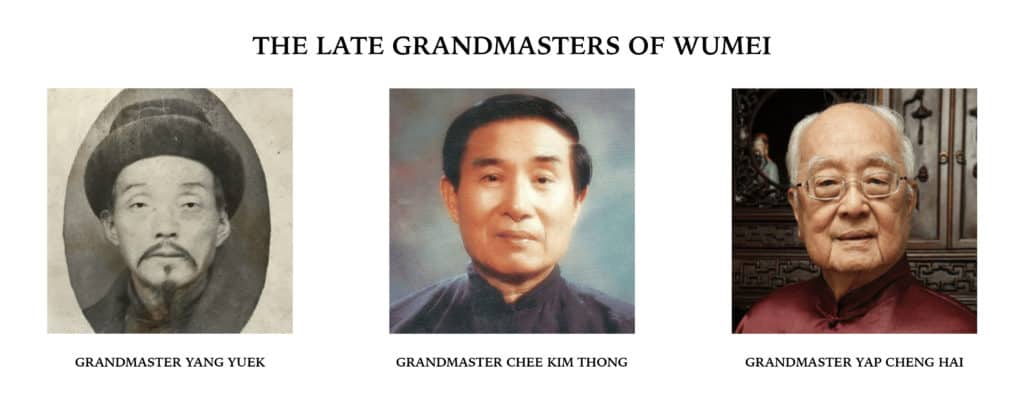

According to our oral history, as related by grandmaster Chee Kim Thong, he learned Wumei from a master by the name of Yang Yuek (Yeung Yoke – Cantonese) in Putian, Fujian. By this time, GM Chee was in his mid to late teens and had already been taught the WuZu (5 Ancestors) system. GM Yang was already in his 80’s, but still active (this puts the timeframe around the early 1930s). Yang Yuek was a very slightly built man, about 160cm (5ft 4in) and about 60kg, but had tremendous power and a reputation in many encounters where no opponent could come within 3-steps of him. GM Yang had a successful business dying cloth and silk, and he also had a large class of about a few hundred students learning Wumei.

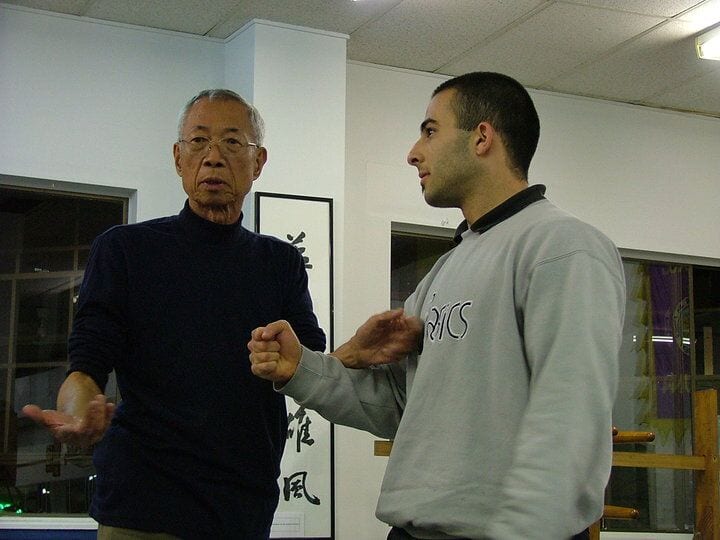

GM Chee came to Malaysia towards the end of the 2nd World War and settled in Dungun, a town on the east coast of Malaysia. He then taught WuMei to his first disciple, GM Yap Cheng Hai. This was in the early 1960s. My father, GM Yap Cheng Hai then taught me (Yap Boh Heong) the art of WuMei in the ’70s’. I have been practicing the WuMei forms diligently but without fully understanding them until 2006 when a spark of realization ignited. The discovery and self-learning continue until the present.

Although GM Chee taught WuMei to others, the number of students who learned the art was minimal, as most of them focussed on WuZu or the other styles. As such, those with a more profound knowledge of our lineage of Wumei number are in the handful. Today. It is fair to say that our lineage of WuMei is rather rare.

Footnotes

[1]: Arts taught by GM Chee: GM Chee had six masters, he was taught Monkey Style by his grandmaster at a very young age, and after that, he studied Chang Quan (Long Fist) a northern style by master Toh I Chuan. Later in his early teens, he was taught WuZu (5 Ancestors) by Master Ling Xian, followed by Yang Yuek, who taught him WuMei. After that, he had a master that taught him BaiHe (White crane) and traditional medicine, and finally, It Sim who taught him the arts of WuJi Quan and Luohan Rhou Yi Quan.

[2]: WuMei and Wudang: the Wudang influence can be seen in reference to the five elements. In our lineage, one of the WuMei forms is also known as the WuXing Palm. Furthermore, the WuMei forms of which there are only five have elemental names. Not fire, wood, water. But they are named after (some mighty) forces of nature, such as wind, thunder, lightning, rain/storm. This is manifested in the movements of the forms and the quality of its internal energies.

[3]: A Rich period of development: Shaolin Kung fu is a practical art, meaning it’s pointless to argue theory. The key philosophy is not how complex or sophisticated the techniques are, but: “Do they work?”. What are the circumstances where they work? And of course, the techniques to defeat a larger and stronger opponent are different from those to overcome a more sophisticated opponent who has speed, internal power, etc. Hence the opportunity offered by Shaolin at that time, with the myriad styles, would have allowed martial artists to experiment, research, and refine their techniques or develop entirely new systems.

[4]: Two WuMei Anecdotes:

1. Lady in the Blue Dress. This story is very prominent in our (Chee Kim Thong, 5 Ancestors) oral history. The founding masters of the five arts that made up ‘5 Ancestors’ met regularly in a courtyard to discuss and test their theories and techniques on how to merge their various styles. One day a young lady stopped by to observe. Soon she started giggling. This continued for a while, and it annoyed the masters, so they asked her what she found so amusing. She replied, “All of your techniques are too ”hard”, you should be more ”soft”. Understandably, this annoyed the masters, and they asked her, “Would you like to demonstrate for us?”. She agreed and promptly overcame the masters. This caused much-heated discussion among the masters, and while they were thus engaged, she left. By the time the masters had realized, she had already gone. They never got her name, style, or who her teacher was; they referred to her as the “Lady in the blue dress.” As a result of that incident, the five masters incorporated a fair amount of ”soft” techniques into our lineage of the 5 Ancestors that persist to this day.

2. The founding Stories of BaiHe (White Crane) and Wing Chun: In the oral history of BaiHe, the identity of the founder is never mentioned, but it’s accepted that the founder was indeed a woman. From a theory expounded by GM Yap Cheng Hai, he suggests that BaiHe is not a single art but a combination of various forms of indigenous Fujin arts, and this could have taken place in Southern Shaolin. Furthermore, WuMei was acknowledged to have sought refuge in a White Crane temple, somewhere in Yunan/Szechuan.

Wing Chun’s founder Yim Wing Chun, was supposed to have learned her art from a lady (WuMei), and some lineages of Wing Chun accept WuMei (Ng‐Mui) as their great ancestor.

[5] Qing court fears Southern Shaolin: The Generals appointed by the Qing to defend southern provinces in China had constant battles with Tibetan invaders from the West. So when Southern Shaolin managed to defeat the troublesome invaders with a small group of 128 monks, quite a few senior officials were embarrassed. They were also jealous that Southen Shaolin received a reward, a royal seal, that gave any edict/law it imprinted, imperial authority. Hence they plotted and tried to turn the Emperor against the temple.

[6] The Betrayer: The monk known as Bak Mei (White Eyebrows) According to various accounts, Bak Mei, together with WuMei and three others, were among the five Elders that escaped from the first sacking of Southern Shaolin. They then reformed Shaolin and plotted against the Qing. Bak Mei was given the task to infiltrate the Qing court, which he succeeded. From here there were two versions of the story:

1. While inside, he realized that the Qing was too powerful to defeat, and gave up on his mission.

2. That he actually collaborated with the Qing and led their army to the 2nd Southern Shaolin, and hence its destruction. Some say he was blackmailed into doing so, as the Qing threatened to kill his family and those close to him (including his followers)

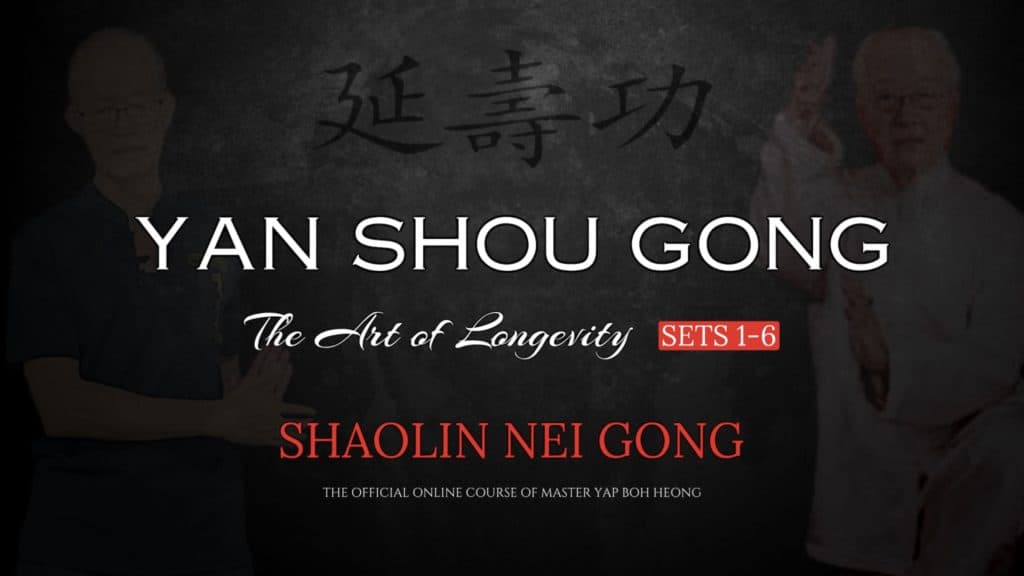

Learn the authentic Nei Gong practices of Southern Shaolin Kungfu

Very interesting

Such great read. Thank you Kieren for sharing and everyone inputs.

Very instructive enlightning

Very interesting thank you ????????????

Thank you so much .

As i follow your work and find it very useful as I am a hardcore lover of martial arts and a practitioner .. As always Great Job … Thank you fromthe core of my heart and Respect????

Thank you for sharing….Fully Respect

This is a well written and comprehensive article. I do not doubt that it would have taken a considerable amount of time to formulate such information and present it in this manner. Wumei is undoubtedly an art that has been kept secret for many years, and there seem to be many secrets contained within the system, and it’s history. Thank you for your hard work.

I enjoyed the history and stories of Bakmei betraying the ancestors before Wumei killed him. It is a story I have never heard before. Great job martial man.

Thank You

Very well done. I practice Qinxi Tang Wuzhu Bai He Quan (disciple) and Nan Chang Taizhu Shaolin Quan (enter the gate student) in Taiwan. Both arts are of Fujian origin. Thanks for posting, it would be great to view some of your forms; have any videos to post?

Can you prove the existence of Ling Xian?

Existence of Lim Xian,

We have a photo portrait of the man, at our Kwoon in Kuala Lumpur. We know of his existence through first-hand oral history from Grandmaster Chee Kin Thong, who trained personally under the man.

(author of the above article)

Undoetunately there was no other hard evidence, even in China! Lim Xian involved in anti0Japanese activities during WW2, and he was from a well to do family. In either case, it owiuld have meant little information was available or was destoyrf duting the Cultural Revolution,

love to learn different forms since im 74 years young looks it is easy on the body thank you will be looking to learn

????????

how to contact master Yap Boh Heong

Hello @themartialman ! Can you recommend any good teachers to learn Wumei from? Does Master Yap Boh Heong give online courses??

Hi Rachel, where are you located? I recommend starting with the Yan Shou Gong (Shaoling Nei Gong) online course first with Master Yap, as this is a prerequisite to learning Wumei from him. You can find out more information here: https://themartialman.com/courses/yan-shou-gong-the-art-of-longevity-sets-1-6