Cause VS. Effect

One of the problems I see with the instructions provided in the internal arts is that students are often only taught the “effects” of the practice and are rarely taught the “causes.” This is problematic because an instructor who only shares the effects of their training guides students to develop nothing more than conceptual ideas and even counterfeit skills rather than something tangible.

If we look at this issue from another perspective, for instance, if I were to try and explain how it feels to be intoxicated to someone who has never drunk alcohol before. I could say to them:

- “When drunk, I feel like I have no coordination.”

- “I feel that I can’t see as clearly.”

- “I feel drowsy.”

- “I feel a loss of balance.”

- “I feel like I’m slurring my words.”

- “I feel more talkative and more self-confident.

- “I feel like I want to initiate a fight.”

After listening to my descriptions of the effects, a person might attempt to copy the feelings I previously described. So they begin bumping into things, moving without coordination, and pretending to lose their balance. In addition, they might try to be more talkative, speaking loudly and even acting aggressively toward others. However, unknowingly to them, regardless of how they “act,” they would still only be simulating the effects of being drunk. They would never experience what it’s like to be intoxicated until they have actually consumed some alcohol.

Let’s take another example. If I were to go through the process of inflating a bicycle tire, I would use a bicycle pump and fill the tire with sufficient air until the tire became inflated and could support my weight safely during riding. The tire would expand and become pressurized full of air because of the process of filling the tire using a pump; this is called the “cause.” I would not tell the tire to “create a feeling of expansion and fullness of air,” as only describing the effects of inflating a tire wouldn’t help or make for an enjoyable bike ride.

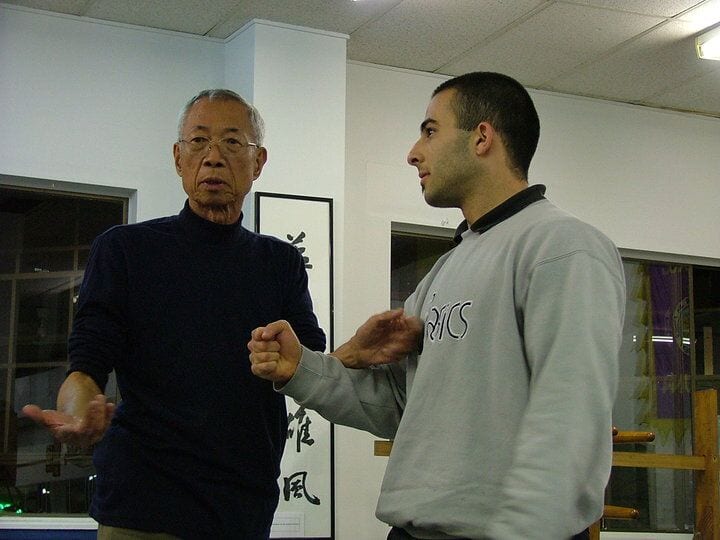

Likewise, if I asked my student to apply force onto my body so that I could demonstrate my rooting skills, and after my student tried hopelessly to push me over, I then explained to him, “to achieve this skill, you must create a feeling of emptiness, so the other person’s force does not affect you” or “experience fullness inside your body so that your energy can support their force.” In this instance, what I described to my student may be accurate; however, they are only feelings and the “effects” resulting from the correct practice. If I want my student to develop the same rooting skills, I would need to teach them the exercises I had previously trained, aka the “causes.” Then, after my student diligently trained in the same method for a sufficient amount of time, they would acquire some kung-fu and could demonstrate the same rooting skills and experience the effects I previously described.

Therefore, for students to succeed in the internal arts and develop authentic skills, they should understand the difference between cause and effect. “One must first taste the liquor to fully understand what it’s like to be drunk.” – metaphorically speaking, of course!

I am very interested to learn the ancient Chinese martial arts